I recently returned from an amazing trip to the Republic of Ireland—a vacation mixed with research for my current novel. I’ve been back for almost two weeks now, yet my days and nights are still turned upside down. In the middle of the afternoon I’m falling into a coma where remnants of the Emerald Isle rush past in delicious snippets of sight, sound, and glorious green. If there’s anything Ireland is, it’s green.

As a redhead with Irish roots, I’ve wanted to visit Ireland from the time I was a small child. When teased about my freckles and orange hair, my mother would tell me about the Land of Redheads where Carrot-tops, Pumpkin-heads, and Irish Setters reigned. All the better that the land had no snakes.

For as long as I can remember, Ireland has lived as a mythical place in my being, a magical realm alive with spirit. Land of the bard, the storyteller, and the seer. Land of the Druids and the dreamers. Land of the Kings of Tara, of Catholicism, Protestantism, and old Pagan religions. A land so incredibly beautiful that it couldn’t possibly exist.

I’ve spent considerable time in the neighboring Wales researching her culture and Celtic mythology, as well as enjoyed many visits to England. More than once, I’ve stood on the Aberystwyth shore and looked across the Irish Sea, but never traversed those waters until now.

My expectations were ridiculously high, yet the island was even more stunning than I had imagined. As a potato-loving, ale-drinking, shade-seeking redhead, I loved the bogs, the moors, and the mist-laden forests, the rough seas, the rain, and the cool damp weather. And I loved seeing more of my carrot-topped kind. To those of you non-redheads (in the U.S. that would be roughly 98% of you) this longing for Ginger kinship must sound downright bizarre. But if you’re a redhead, you likely relate. We’re a tiny minority—a strange species that throughout history has been at odds with the rest of humankind. In medieval times we were deemed witches, vampires, and wolves. We’ve been considered good luck, bad luck, sex fiends, vixens, devils, fairies, and just trouble. We’re told we suffer from bad tempers and moral degeneration. We’ve been burned at the stake and had our heads rubbed for luck. Doctors tell us it takes more anesthesia to knock us out and that we feel pain differently than others. The fairest of us shrink from ultraviolet light. We speckle and burn and blister up like something out of the Night of the Living Dead, yet our friends still wonder why we slather on sun block and wait until dark.

And while we can’t exactly explain why we are the way we are, scientists are happy to do that for us. They’ve concluded that the main factor for producing red hair lies within the MC1R gene, and that the Irish carry the highest ratio of the gene in the world.

My mother had spoken the truth: in Ireland, to be a redhead, is not only considered good fortune, but to be one who “has the Irish.” There’s a kinship there, a fondness, a welcoming home. But even in Ireland, we only account for approximately 10% of the population. Ireland is not only the Land of the Redhead, but of a Celtic People of all shapes, coloring, and sizes—a spirited country with a tumultuous past.

What touched me the deepest about the Irish was their reverence for the land and their ancestral heritage, both inextricably entwined. Like the redhead, Ireland has had a long complicated history. She has survived Viking and Norman invasions, eight-hundred years of British suppression, the Great Potato Famine, the Irish Civil War and the Irish War of Independence, yet through it all managed to hold onto her strong Celtic culture and traditions. She has battled the dark side of humanity and remained standing

The island is a veritable cornucopia of ancient artwork, Iron Age standing stones and medieval castles spread across the landscape like jewels to be discovered. The greatest concentration of megalithic art in Europe lies in the Boyne Valley at Knowth, an ancient passage tomb marking the spring and autumnal equinoxes.

From the magnificent yet harrowing Cliffs of Moher, to the precarious twists of the Dingle Peninsula, Ireland is a place that demands that —like her people—one grasp for life with hands wide. Turn down any country lane in search of something—anything—and you won’t be disappointed: a forgotten castle, a stone circle, an abandoned medieval church, a field of wild blackberries, a goat with questioning eyes. It’s all there for the taking, as long as you can face the adrenaline rush of a car careening toward you down a lane at 120 kilometers on the British side of the road. These tiny lanes are a rite of passage, not for the claustrophobic or faint of heart. I learned long ago in Wales to pull in my side mirrors and hit the gas. Strangely, magically, downright mystically, the cars seem to glide through each other and sail on past. Don’t try to find logic, to analyze or dissect, just trust in the resolve of the natives. While new motor ways now cut across the Island to join major cities, the country roads remain narrow and winding, curving wildly around hill-forts and ancient ruins so as not to desecrate or encroach. Sheep have the right-away along with formidable herding dogs who will send you right back down the lane from which you came, even if you have to back the whole way.

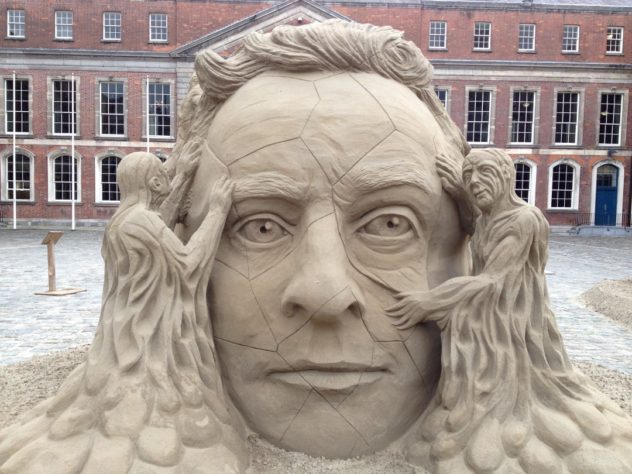

Even in the cities, much of the artwork reflects Ireland’s symbiotic relationship with her land. Inside the walls of the Dublin Castle, I found vast sculptures of sand, masterpieces providing reflections into the human spirit. While breathtaking in scope, these sculptures were temporary thoughts soon to be swept away for the next profound expression.

With four Nobel prize winners— William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, and Seamus Heaney— and the literary pedigree of the likes of James Joyce, and Oscar Wilde, the Irish have made an incredible mark on world literature: Joyce with his brilliant stream of consciousness, Beckett with his existential postmodern starkness, Shaw with his biting satire, Wilde with his eccentric wit and dark imagination, and Kate O’Brien with her challenges to gender inequality and Irish censorship. The list is long and impressive—writers unafraid to speak their minds and invoke change—all unruly in their own right, Irish in nature. Poets and rebel leaders, Patrick Pearse, Thomas MacDonagh, and Joseph Mary Plunket were at the core of the Easter Rising in 1916, their execution pivotal in gaining public support and ultimate victory for Irish Independence from England. I visited Kilmainham Gaol, the prison where these insurgents were held and then executed, and their stories stayed with me for days.

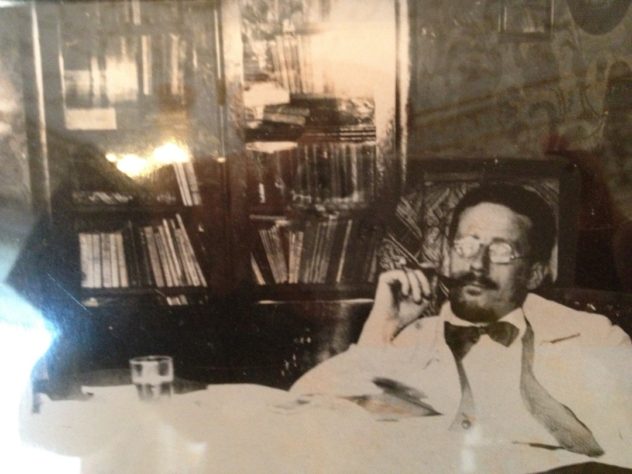

At the Dublin Writers Museum, Bram Stoker was featured under “Masters of Sensation” alongside Charles Robert Maturin and Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. And while his fellow Dubliner, James Joyce, is said have put Dublin on the map of world literature, Bram Stoker gave the world one of the most formidable antagonists of all time—Count Dracula.

Dracula was one of the first novels I ever read and it remains among my favorites. It sold more than a million copies when first released in 1897 and has never gone out of print, yet at the time of its release the Manchester Guardian wrote that Stoker had made “an artistic mistake to fill a whole volume with horrors.” The reviewer accused the author of being behind the times, asserting that “Man is no longer in dread of the monstrous and the unnatural . . . old superstitions of the past have an unhappy way of appearing limp and sickly in the glare of a later day.”

One hundred and sixteen years later, crossing into a new millennium, Dracula continues to be one of the most popular and analyzed Gothic tales of all time. Clearly the 19th Century reviewer did not see that Stoker’s work went beyond mere genre labeling and that society will always need its dark literature to touch upon her deepest emotions, needs and visceral instincts. Perhaps he didn’t understand that, as in nature, the human experience is much about balancing the light and the dark and that these truths are inherently inescapable. Millenniums will pass, yet we will still need our monsters to face so that we may emerge victorious.

Picasso once said, “I don’t know what inspiration is, but when it comes I hope it finds me working.” Inspiration seems to find me on vacation, when I’m out and away from home, in a new city or a foreign land. The same was said about Stoker who found inspiration through travel. Imagine my delight to find out that both he and James Joyce were also redheads.